On the decline of religion

Dear M,

Frederick Forsyth says in The Biafra Story that when the British created Nigeria it was comprised of three primary ethnic groups. There were others too, but the main three were the Hausas, the Ibos, and the Yorubas.

Up north, well before the British took over, the Hausas had already been conquered by Muslims. The Muslim Fulani empire had invaded the Hausa kingdoms between 1804 and 1810, and had imposed a kind of top-down society, with emirs on top and a lot of ignorant slaves and peasants on bottom. Rules were given without consulting the people, wealth was stolen to bolster the ruling class, and the few schools they had existed only to keep the top of society in charge.

The British left things this way because they didn’t have much choice. Like the Scots-Irish colonized the American West and Lord Clive conquered India, British explorers and businessmen in Africa went first and established something not too unlike a colony. Other European countries were grabbing African land “officially,” however, and when it became clear that the French and Germans and Belgians were expanding and wanted the British spots for themselves, the British government backed what British merchants had already claimed. Nigeria hadn’t even been explored when it became a British territory. It was all claimed in a haste to keep the French out.

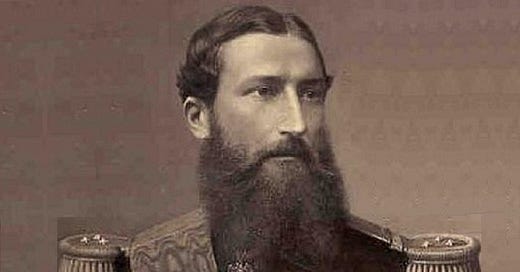

Thus the Hausa remained in a state of subjection, because the British were too few to maintain any kind of garrison*. A few hundred soldiers led by Sir Frederick Lugard crushed any and all who stood in their way; and once they’d sawed the Muslims down with the Maxim gun and such, they needed Muslims to run things. So the powers that be just continued to be. Emirs keep the poor down and ignorant, believing that education would mean uppity peasants. They answered to the British on the big issues, and most of the small ones were left to their own choice.

In the southeast region of Nigeria almost the opposite happened. Free from the menaces of the Muslim Fulani, who were sweeping south until the British stopped them in 1840, the Ibo were “colonized” by merchants and missionaries. Unlike the conquered and downtrodden people of the north, they still retained a strong traditional society and were used to having elders consulted for practically everything. The missionaries established lots of schools, the general trend toward education caught on, and by independence year in 1960 Forsythe says they had 842 schools compared with the north’s 41. When the east seceded from Nigeria in 1967, they had more lawyers, doctors, and engineers than any other country in black Africa.

What this meant was that by the 1960’s, the Ibos of the southeast were directly involved in almost every aspect of modernization. They had all the professionals, and the professionals flooded west and north, but mostly north. The north had nobody to run things or build things. They viewed education as a threat to the social structure, and saw the Ibo almost as the Germans saw the Jews in 1930. Jealousy was thus rampant, and suspicion to go with it.

This is one reason why parliamentary democracy didn’t work for Nigeria. First off the ethnic differences and educational disparities were simply too big to go smoothly. But second the ultraconservative Muslim north had over 50% of the people. So regions were established in a loose federation and immediately became rivals. Cheating on the census led to further suspicion. Counts were radically low for taxes and radically high for voting. Riots were staged as a pretext for emergency moves and power grabs. Eventually the north began pogroms, killing the Ibos willy-nilly, and a brutal civil war ensued. Nigeria to this day has problems between rival ethnic groups. I assume it always will.

But this brings up another point. If differences in education led to so much resentment between Nigerians, I believe it does today in American society too. The missionaries were the precursor to the modern university. They established little schools wherever they went, teaching kids to read so they could understand the Scriptures, and this turned into teaching math and writing, and skills, and good habits to go with them.

In an impoverished world this left the Christians unparalleled. The Bible overwhelmed all other published literature to an impossible degree. Thus common themes developed in the evangelized world — Jewish ways to look at God and production and justice and family and morality in general. Church, the media system of the old world, was attended every week by a vast majority of people; and in Catholic Europe, this meant a centralized message. One book for the most, one church, one civilization.

But we no longer live in an impoverished society, and the machine gun which was the missionaries’ school, empowering its students to go and conquer the world, has become something more like a slingshot. First off books became cheaper to print, and instead of books being hoarded by the rich, even the poor can get libraries now; and if they’re in the boonies, Amazon will deliver it to them. And the number of books to choose from, each with its own moral gist, is innumerable. The freedom for every man to write a book is the freedom for every man to read a book; and the end result is that few of us read the same books.

Second is the fact that schools have been taken over by the states, and the mass hoarding of wealth has allowed them a critical advantage in teaching sciences, maths, and all kinds of other subjects — perhaps most importantly the national myths and narratives. Teachers’ unions have developed alongside them, and their adherence to liberal ideas allows teachers with socially offensive views to keep their jobs in the face of protesting parents. The Ibos were colonized by missionaries yesterday, and the children of the missionaries are colonized by the state of California.

Third, the once-important sermon you’d hear at church, once a week, and the Sunday School that went with it, are overwhelmed by a whole slew of other moral lessons — which come from TV shows, magazines, movies, and music; a good number of them better written than the Old Testament. The church’s defeat by the music industry seems especially dire, but the real damage has been done by Hollywood. The stories of David and Goliath and the woman at the well have been outdone by The Avengers and Mad Men — stories by writers well outside the church, with their own agendas, and billions of dollars to play with. Poverty was always the life-blood of the church, and capital is generally its killer. A kid will hear a dozen, maybe two dozen non-Christian stories with non-Christian morals before he hears one sermon at church (if he goes). And if he does go to church, he’s likely to forget the sermon anyway, because very few pastors are actually interesting. Certainly not as interesting as Star Wars, or Stranger Things.

The church still has one great advantage, and (aside from its claims to objective truth, a universal narrative and the afterlife) it’s that movies and music and magazines don’t provide much of a community beyond random enclaves of fanboys and hipsters; and if they provide a kind of common culture, as you get older they give you fewer people to practice it with. Thus the people at church are less hip, many times, but much healthier (psychologically) and heartier than the average liberal (as long as you’re not a United Methodist), and have a deeply-felt resentment against the walking damned — who are generally cooler, more interesting, many times “better educated,” more upwardly mobile, have the bigger institutions on their side, and are generally richer. A similar resentment, I believe, to what the pagans felt against third-century Christians, and to what the Hausas felt againt the Ibos.

This resentment (I presume) will grow because Christians refused to go into learning and “the arts”*. To most seriously devout Christians, the Bible is the height of all learning, the Holy Spirit is the dispenser of all wisdom, and the church is the heart of all culture. It may have even been Christians’ reverence for God that made them trail behind men. Christ said it was hard for a rich man to get into heaven, and I believe Him. He knew that once we became rich, Netflix would be more interesting than Pilgrim’s Progress.

Thus we aren’t in the collapse of a religion, but in its eclipse. Like the family and sexual ethics were mangled by birth control, we experienced a revolution in technology — and forgot that all serious revolutions in technology precede revolutions in morality. The internet was never a new way to deliver data, but a new way to amplify the life-force of whoever mastered it first.

Yours,

-J

PS Leftists love to complain about colonization, and maybe they should. But the alternative to being a British colony was being a French or Belgian colony. Which the Nigerians nearly were. I remind you that during King Leopold’s reign, millions more Africans were murdered than Jews during Hitler’s Germany.

*The reason the British had too few people to maintain a garrison is because by 1875, Britain’s liberal government considered colonies in jungle backwaters (and I quote Forsythe here) “an expensive waste of time.” The Royal Commission had actually advised the government to dump its middle-of-nowhere colonies, but the government wouldn’t just give them up, and it was reluctant to make any more.

This philosophy went up in smoke, however, when the British merchants got armed and organized after French advances; and the little fighting force led by Sir Frederick Lugard, with a little help from the local British consul, ended up beating the French and effectively conquering Nigeria — a story very similar to the way the British conquered India.

Of great kings and queens very little can be said about the British or anybody else. But like Americans Brits had lots of spirit and less constraints, and random people were able to do what their leaders didn’t have the balls or the brains for. There’s no guarantee you’ll ever get a great king. But there’s a high chance that if your king gets out of the way, your savior is laying in a crib right now, and you’ll find out who he is when you need him.